For D.L.

For the rest of the world, it was just another year of normal duration. For my father, it was the year during which nearly every room in my grandparents’ plantation house was festooned with a small red box featuring a cheerful black chef holding a steaming bowl of what resembled grits that miraculously went from pot to spoon in a mere two and a half minutes. However, Grandma Viny drew a line in the tiger maple floors refusing to have that box in her kitchen.

Grandma Viny eschewed her European roots, identifying herself solely as a Southerner. She would have you believe our people emerged from the dank southern soil, just in time to fight in the War of Northern Aggression. She had anecdotes but no documents.

She regarded the 1859 house to be our ancestral home, however the title deed dated December 11, 1929, listed my great great grandfather as the buyer and Cyrus Nutter as the seller. Despite the applicability of the surname Nutter, we were not related. Grandma Viny insisted the title also conveyed Cyrus’s heritage to us, never acknowledging that heritage mostly consisted of his being an adept alcoholic who was reduced to accepting pennies on the dollar for the house and surrounding two-acres. He had already drunk and sold off the plantation’s other 58 acres. For Grandma Viny, there was no inconsistency between her story and reality. “Somethings have to be felt as opposed to known.” If one argued further about our birthright, such heresy would be rewarded with a swift slap of her enormous wooden grits spoon.

“The important thing about grits is the grit it takes to make it. We Southerners have it, those up North don’t. “Anyone can scramble eggs, fry bacon, toast toast and call it breakfast. That’s not breakfast; that’s laziness. Grits require you to stand over a hot oven for half an hour committedly stirring.”

She wiped her dewy brow; sweat always seasoned our grits. Not just Grandma Viny’s, but also Lucy who served our family for at least two generations. Once Grandma Viny was done with her history lesson, she would hand the wooden spoon to Lucy who was expected to stir the grits for the remaining 28 minutes, only to watch Grandma Viny run her spoon over the grits’ surface, like a sapper, searching for lumps.

“But patience is a dual-edged sword as it can easily slip into contentment—the Southern man’s malady.” Despite the chill running down my spine, I was not the target of her disappointment, but rather my father and his father, Grandpa Gerald, who shared a single epithet: “contently content.” Grandpa Gerald was a quiet man with a small probate and trust law practice in Charlottesville. “How a man who spends his days concerned with other people’s legacies, could be so ambivalent to his own, I will never understand,” Grandma Viny sighed. When courting, Grandpa Gerald found Grandma Viny’s dogma to be invigorating; now in the twilight of their marriage, he found her tiresome and was forever checking his pocket watch for the time when it would be considered acceptable to go to bed without criticism.

Grandma Viny had once been pleased that my father received a Bachelor’s in agriculture from Virginia Tech. She had visions of him restoring the plantation’s lost lands, even though this would require leveling the post-war housing development. She imagined him seated triumphantly on a tractor knocking down those horrid little houses as rows of corn bloomed behind. She was crushed when he opted for the security of a research position at a food company that was responsible for “the-abomination-of-a-breakfast-cereal-that-pretends-to-be grits-but-is-made-with-wheat!” My father knew there was no point in arguing with her and simply pined for the day when we either moved out or Grandma Viny moved on.

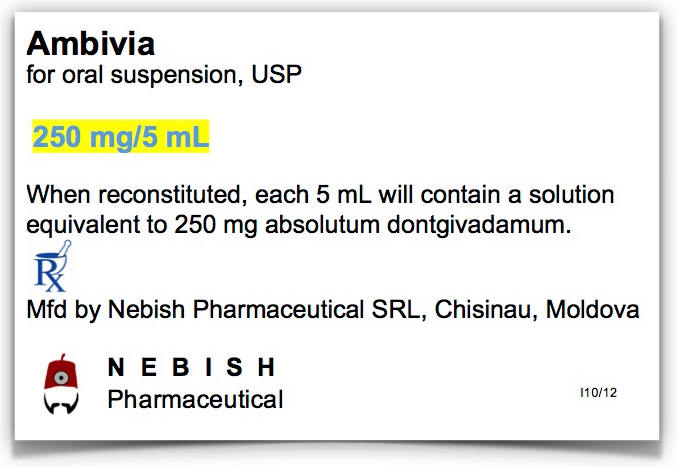

This changed the day my father burst into the house, announcing that the Food Industry Association had bestowed on him their highest award: the Adler Bowl for Achievement in Processed Foods (Breakfast/Brunch Division) for his invention of 2 ½ Minute Cream of Wheat.

Grandma Viny looked at the silver bowl as if it was contagious. Instead of congratulations, Grandma Viny was stroke silent, feeling the wrath of generations of Southern women who slaved over stove or fireplace stirring their grits until their wrists ached. She was determined to be their voice.

What Grandma Viny had not anticipated was the ovations her son’s accomplishment afforded her. “No more endless stirring,” her friends would say, as if they had been paroled.

Even Claire Beaulieu, a true woman of the south, was impressed. Claire had unimpeachable credentials; on her mother’s side was an ancestor who sailed up the James River on the “Godspeed” in 1607. Her father’s people had been expelled from Canada and morphed into Cajuns who would one day send one of their own to Congress on the eve of the Civil War. With the acrid taste of gun powder in his mouth, he galloped south, was appointed a colonel, rallied a battalion of New Orleans gentlemen, and sped back north. While Colonel Beaulieu may have been an eloquent speaker, his words did not save him from a sniper’s bullet as he tried to enthuse his soldiers to be the first in the field. His barely used sword hung over the mantle in the Beaulieu mansion sitting room, above their family crest: Semper Citius (Always Faster). When Claire Beaulieu requested your presence, you couldn’t decline nor dither.

Grandma Viny fully expected Claire Beaulieu’s censure for her son’s sin. Her surprise was almost lethal as Claire Beaulieu, who traditionally did not acknowledge any accomplishments not attributable to a Beaulieu, flashed Grandma Viny a smile wider than a Mississippi oxbow. “Felicitations, my dear Viny. What your son has accomplished is nothing less than a triumph! Now every Southern child can have a warm meal on a cold day. A mother’s love in less than three minutes, imagine that. If only my good-for-nothing grandson, Billy, who I believe is some sort of subordinate to your son, could invent such a wonder.” What was Grandma Viny to do except take all the credit? She thanked Claire for her kindness and explained that the brains and tenacity were from her side.

Armed with Claire’s praise, Grandma Viny welcomed my father home, heaping praise on him like cinnamon sugar. Poor Dad expected a lecture that lasted way after Grandpa Gerald’s bedtime. Instead, she rewarded him with a warm embrace and a ruby kiss that remained on his left cheek for days. Grandma Viny led him around the house, showing him the rooms decorated with boxes of the miracle cereal, never noting its absence in the kitchen.

As the recipient of an annual award, my father felt time’s dash across the calendar. As the second Thursday in November approached, he knew his term as the holder of the Adler Bowl for Achievement in Processed Foods (Breakfast/Brunch Division) would soon be over and he would be required to announce the next recipient. He affected Granma Viny’s insincere smile as he practiced handing the bowl over, imagining congratulating the smart money’s choice: the inventor of Breakfast in a Jif: Ready-to-Eat-Bacon-and-Egg-Sandwich.

Fearing he was on the precipice of losing her admiration, my father invited Grandma Viny to the award ceremony to demonstrate his resilience and magnanimity. Across the table, he witnessed her receiving the last dregs of fame as attendees congratulated her on their way to the bar.

The final second of his tenure knelled; he checked his blazer buttons and took one final look at his reflection in the silvered side of the Adler Bowl. All things must end, but even time could not steal his legacy; he would always be the 2 ½ Minute Cream of Wheat king.

Standing at the lectern, one hand on the bowl and one hand on a note card, he looked as if Damocles’ sword had cleaved his heart in two. With a drowning man’s gasp, he croaked: “The winner of this year’s Adler Bowl for Achievement in Processed Foods (Breakfast/Brunch Division) is Guillaume “Billy” Beaulieu for his invention of 1 Minute Cream of Wheat.” Snot-faced Billy Beaulieu who was known to root around my father’s desk whenever he was away, smiled at his Grandmother who tried to look surprised.

Like a bruised child, my father sought Grandma Viny’s eyes. He craved comfort or umbrage; what he got was betrayal as she watched people throng towards Claire Beaulieu to offer their felicitations. Imagine, a hot cereal that took less time to cook than to sing Dixie. Do wonders never cease?

Grandma Viny’s head spun like a weathervane in a hurricane, first looking at Claire Beaulieu, then at my father and, finally at me. Swiping a spoon from a waiter who was doling out dollops of trifle, she skipped my father and pointed it at me like an accusation. The torch had passed to the next generation and I felt its embers.