They come as soon as soon as the mall closes. The Christmas lights that have been there since October and will still be up in a month, go off. They throw the tarps over and slide the cables and locks into place as if anything underneath is worth stealing. Then they come to me. Sometimes it is get a watch fixed, but mostly it is for advice. Juan who sells vinyl siding, is thinking in getting into his Uncle’s ice cream business. Tanya, who sells cellphone cases, is in a bad relationship, but doesn’t know if she can do better. Kevin, who sells timeshares, is starting to hear angry voices in his head.

“I work at a mall kiosk,” said no one ever who hoped to get a date. If the girl has extraordinary resilience, she might let me explain I do not sell phone plans, vinyl siding or even wooden religious item. I am basically a jeweler. I am sure people at Kay Jewelers or JBR would disagree. I don’t technically sell jewelry except for the watches that people have left for repair and never returned for. Their customers would be surprised to learn that the professional jewelers sheepishly come down after hours leaving me with repairs that their “experts” can’t fix.

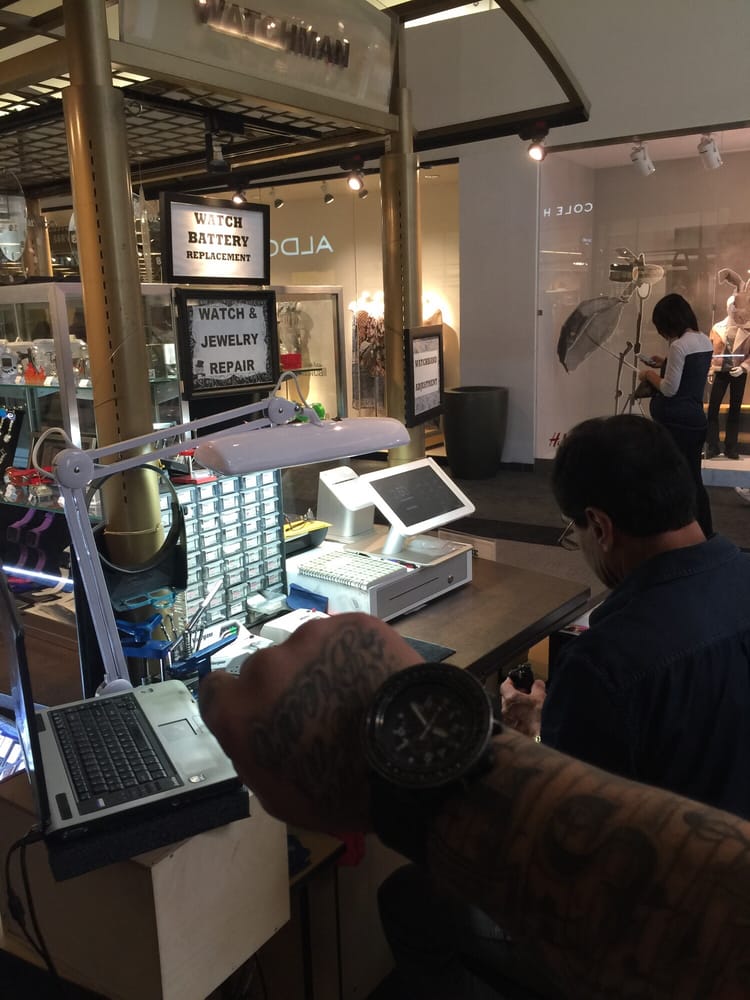

My kiosk is not one of those down a dingy arm of the mall, but smack in the middle of the main concourse, outside of the Foot Locker and the Rue Claire. Enter from the east parking lot and head west; it’s impossible to miss me. There is another kiosk closer to the center of the mall, but it is basically a cart with shelves. It has sold bangles, hot tubs and key chains with all the popular names.

I have seen the other kiosk residents come and go. They show up early one morning with boxes full of products and optimism. They tell me how excited they are to sell [insert useless bauble here] and how this is just the beginning of their road to success.

First comes the kiosk, then a small store and then stores in other malls. I look up from whatever I am fixing and nod. I have heard this all before, but what would be the point of being an asshole? They’ll figure it out soon enough.

And when they fail, they will wait until I throw the tarp over my worktable. They wave to me as I walk by, as if they will still be the next day. They never are. More than one has left a Post-It note with an apology on my tarp. I don’t judge. It is tough to make it working in a kiosk. Focus and low aspirations is the name of the game. Me? I fix watches from crystals to gear work. But I mostly sell and install watchbands and batteries. Nothing sexy. But for someone who needs a working watch, it’s important. There is nothing better than to watch them checking their wrists as they walk away. It may sound corny, but it gives me a thrill to see that. I know—undatable.

Since I could hold something in my hand, I was on a mission to fix it. At first, it was simply the top of a vitamin bottle. Then it was blocks that were arranged in a neat line. I lived in a word that was divided into the broken and the fixed. My father, a physician, had dreams of me being a surgeon. It didn’t take him long to realize his dreams were mere fantasies. Most smart kids distinguish themselves in elementary school. I was in third grade when Miss Temmie declared to my parents there was nothing wrong with being ordinary. I was pleasant enough and I could fix anything she put in front of me. Some people work with their brains and some people work with their hands. My father looked like he had been stung by a wasp and was unsure whether he was allergic. He transferred his dreams and expectations on my sister, Susan. Susan ended up being a psychologist, which wasn’t what he wanted, but was a hell of a lot better than someone whose office is 24 square feet and perpetually smells of grapefruit due to being downwind of the Bath and Body Works.

It never bothered me—my father’s disapproval. The one thing learned from him is there are things that you can fix and somethings you can’t. Every so often someone brings me a watch that fell into the water. The gears are inevitably corroded and it would cost twice what the watch is worth to try to fix it.

The one thing I have in common with my father is the ability to deliver bad news quickly with the right amount of sympathy, without being drawn into debate. I’ve had customers yell at me and insisted that I must have done something wrong or that I was incompetent. I shake my head and go back to my work. They can be upset at me, but that still won’t bring back their watch or fix the fine filigree of the necklace. If he could, my father would have been proud of me. Being mad or sad, somethings just can’t be fixed. The secret is to know the difference.

Somebody knew somebody who knew my friend Brad and told him that there was a job fixing watches and jewelry. Being the person that everybody brought their stereos for fixing, Brad though this would be a good job for me. As I could never make college fit, I figured why not. Brad conveyed that message back down the line. I don’t remember what I expected the Watch Stop to look like, but I certainly as hell did not imagine it to be a glorified fishbowl, defined by shelves and cases that contained watchbands, surrounding a bench with tools and a lamp and a small table with a cash register on it.

If there was a place that deserved the sign: “Dead End,” the Watch Stop was it. This is where my lack of ambition had deposited me. What could be worse than “worked at a mall kiosk” on one’s resume? It would be better to feign unemployment. Swallowing what little pride I had left, I opened the half-door and sat on the chair that someone had duct-taped a pillow to the seat.

I was overcome with surprise when I discovered that I liked the work. I liked to fix things and not think too deeply about it. Replacing a watch battery is just about the right tools and a supply of batteries. At first it seemed meaningless—anyone with the right tools could do it. But that was the point—they didn’t have the right tools. I could tell by the scratches on the bezel that customers tried screwdrivers, knifes and maybe their teeth. Admitting defeat, they come to me and looked relieved when I say nothing, pop the back off, insert the battery and handing it back to them without comment. At most 30 seconds at all and with a simple charge of $9. Technically, if I worked constantly, I was making over $500 an hour. Not too shabby. Watch bands took even less and people seemed to appreciate me not saying anything when they chose the cheaper lizard over the more expensive alligator. An expensive band goes on as easily as a cheap one.

I have fixed phones, calculators, glasses, blenders and pretty much anything that required at least two parts to work in harmony. The hardest part was figuring out how much to charge and explaining to Mr. Schneider why the underside of the table was packed with parts not related to watches and jewelry. He didn’t mind; I made him more money than he reasonably could expect.

When you take the emotion, such as frustration or fear, out of the repair equation, making repairs is easy. That goes for watches, necklaces or relationships. The answer I offer as the night-time visitors wait their turn is the same and is in the form of two questions: Can it be fixed? And: Is it worth it? Other than that, I have no other solution and no other answers. Most of the time it is enough.